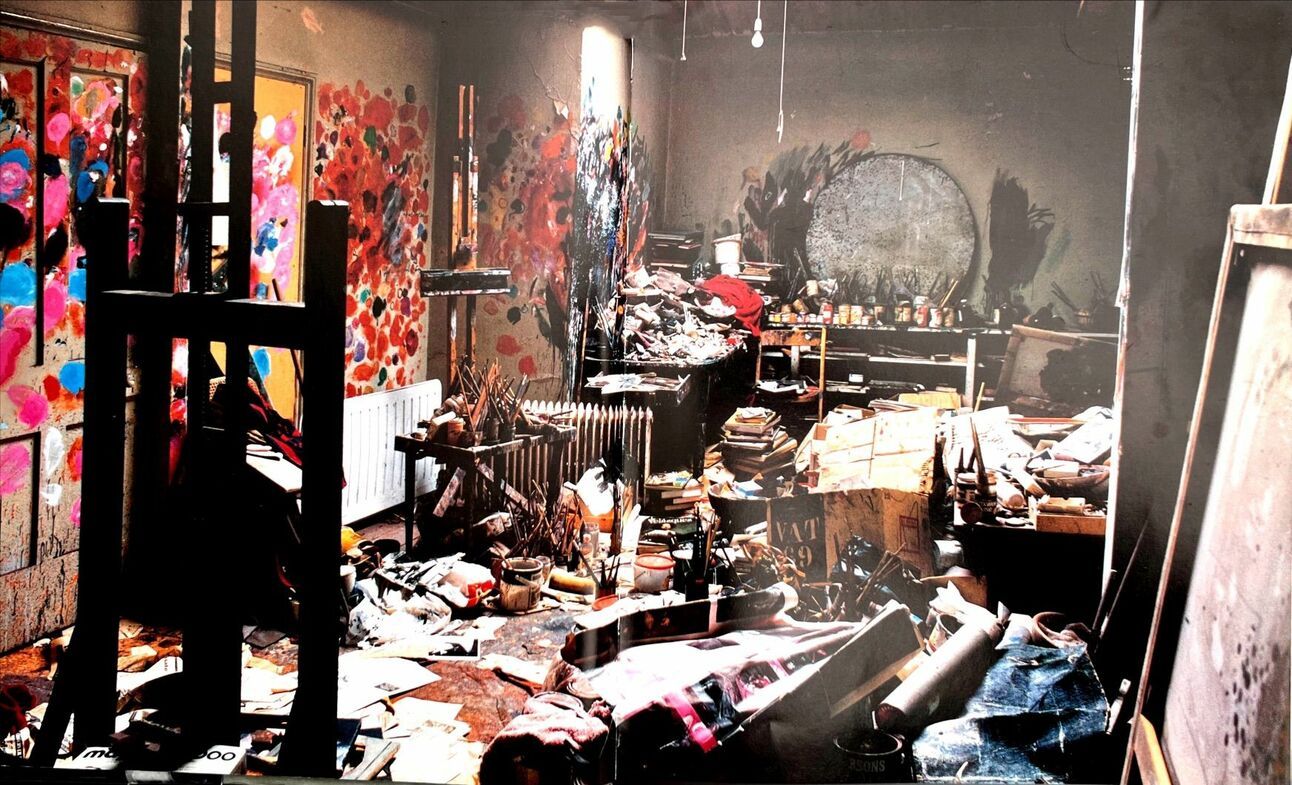

Francis Bacon’s studio at 7 Reece Mews in London. 13x20 feet. Bacon probably designed the large mirror himself in the 1930s when he worked as a furniture designer. Image scanned from Margarita Cappock's Francis Bacon's Studio.

In his tiny London flat, the painter Francis Bacon seemed to think about nothing other than his own work.

He lived in his paintings—his past, present, and future paintings, as if all at once.

Bacon liked to work in series, producing several variations from one source. His serial approach meant he was always looking at his previous work, and also thinking about his next work. As Margarita Cappock puts it in Francis Bacon's Studio (from which the present essay draws all of its facts and images):

“This continuity of endeavor served the purpose of developing favored themes and working out deep rooted concerns. It also reinforced the activity of painting itself as a matter of habit and routine."

I think the unique force and violence of Bacon’s paintings derive partially from the ascetic Lebenswelt he cultivated.

Keep in mind he lived and worked in this flat from 1961 until his death in 1992, long after he became wealthy and renowned. He was not forced by circumstance to live in such a small, modest space.

Into this chaotic atelier, Bacon allowed almost nothing other than painting supplies and his varied source materials: Photographs, books, magazines, etc.

He locked himself into an otherwise closed circuit of his own reflections. He would even write handwritten notes to himself about what he should be thinking about.

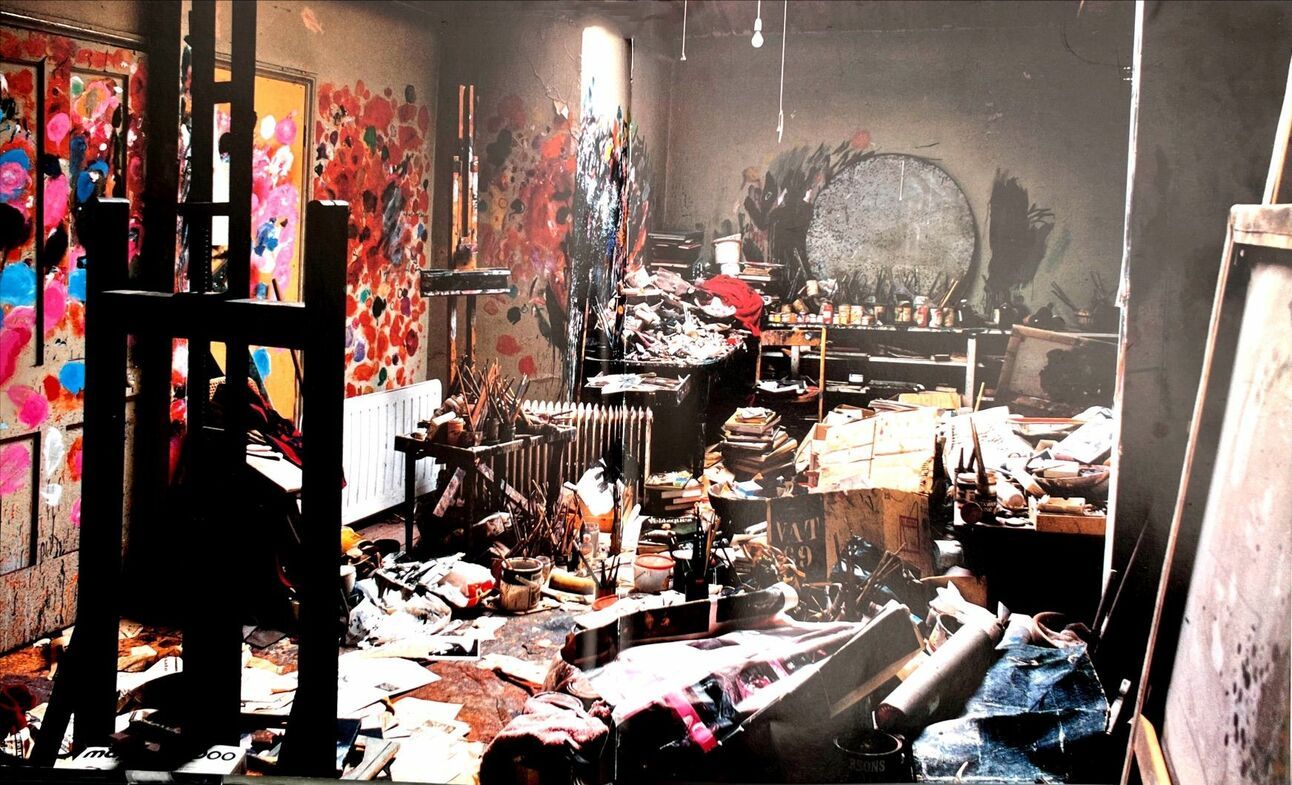

He would post these notes around the space, for instance above his sink in the kitchen-cum-bathroom.

View from the front; kitchen/bathroom; bedroom/living room; staircase. Look closely above the sink, where he mounted notes about his work.

“Think of Crouching Nude 1952,” says one note or, “Remember white marks which mask body,” says another note. These were not "to-do lists." These were guardrails for his attention.

At only 13-by-20-feet, his studio was small but small means concentrated. Bacon engineered for himself a hyper-concentrated petri dish, with no contaminants of distraction but also no escape valves (other than his canvases).

In many of his interviews, he would talk about works he had been planning for a long time. Perhaps one can only envision and faithfully execute unique long-term projects to the degree one completely lives inside one's work. Ideally, one would live in a kind of hermetically sealed, tiny, concentrated pressure cooker. Or at least that's a hypothesis, inspired by the studio of Francis Bacon.

Bring in nothing but the finest inputs, and focus every possible attentional pathway back into the work at hand. Every minute becomes a kind of perpetual duration, an eternity of one’s own. Even focused work for just a few hours can produce this feeling, can it not? It stands to reason that, the more ruthlessly one concentrates one’s entire Lebenswelt, the more everyday life itself can take on this sense of infinite duration.

What would have happened to Bacon’s career had he been subscribed to nine podcasts? Had he been posting his work to Instagram, and Facebook, and Twitter? Pressure would have leaked from the pressure cooker and the violence of his work would have dissipated. We can debate how much the violence would dissipate, but I’m utterly convinced that it would have to dissipate—other things equal.

We are learning to devise novel structures to offset such dissipation, to create even more powerful pressure cookers on the digital plane, but in the absence of novel offsetting structures, I'm convinced that here we are talking about a rigorous, law-like tendency.

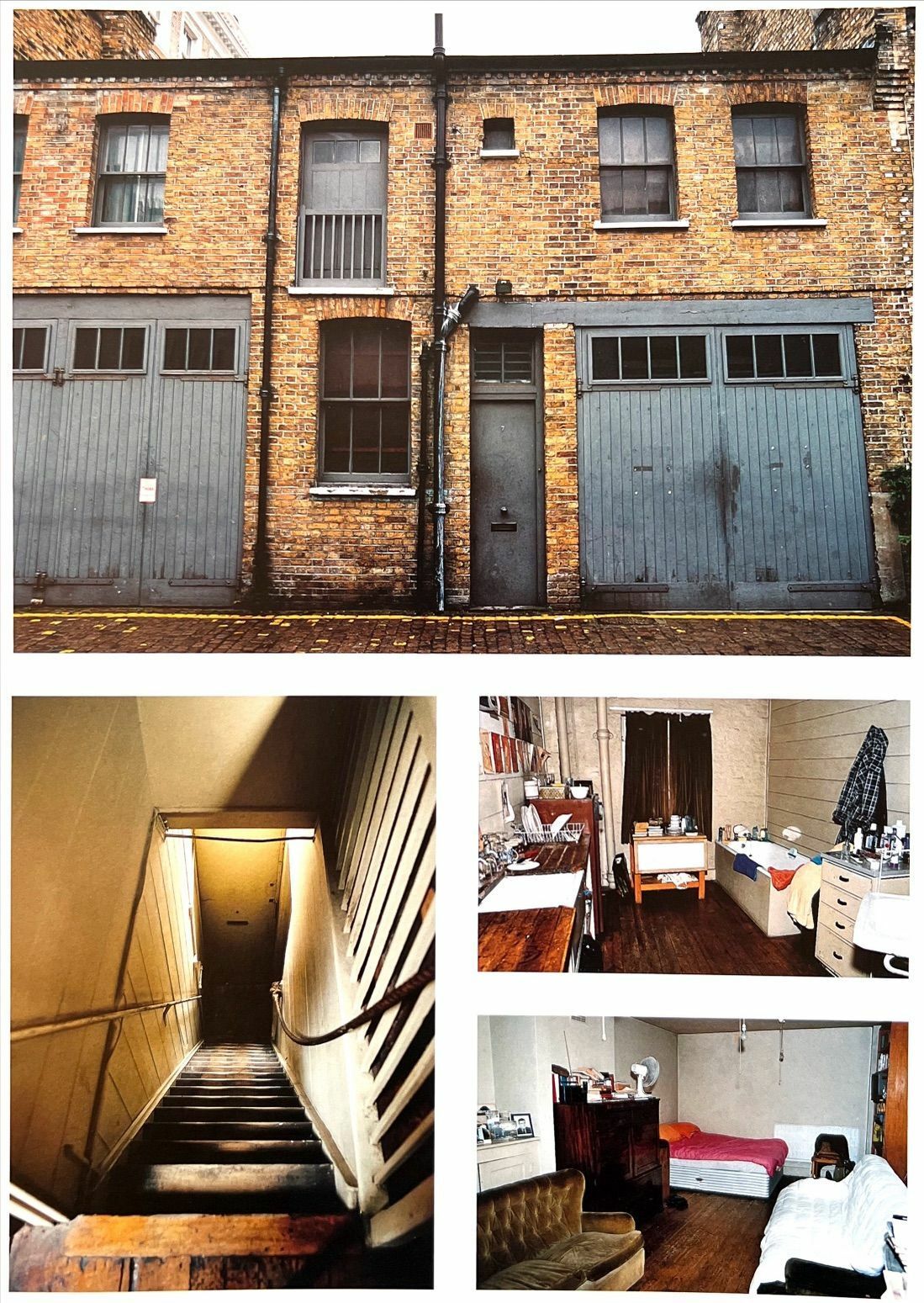

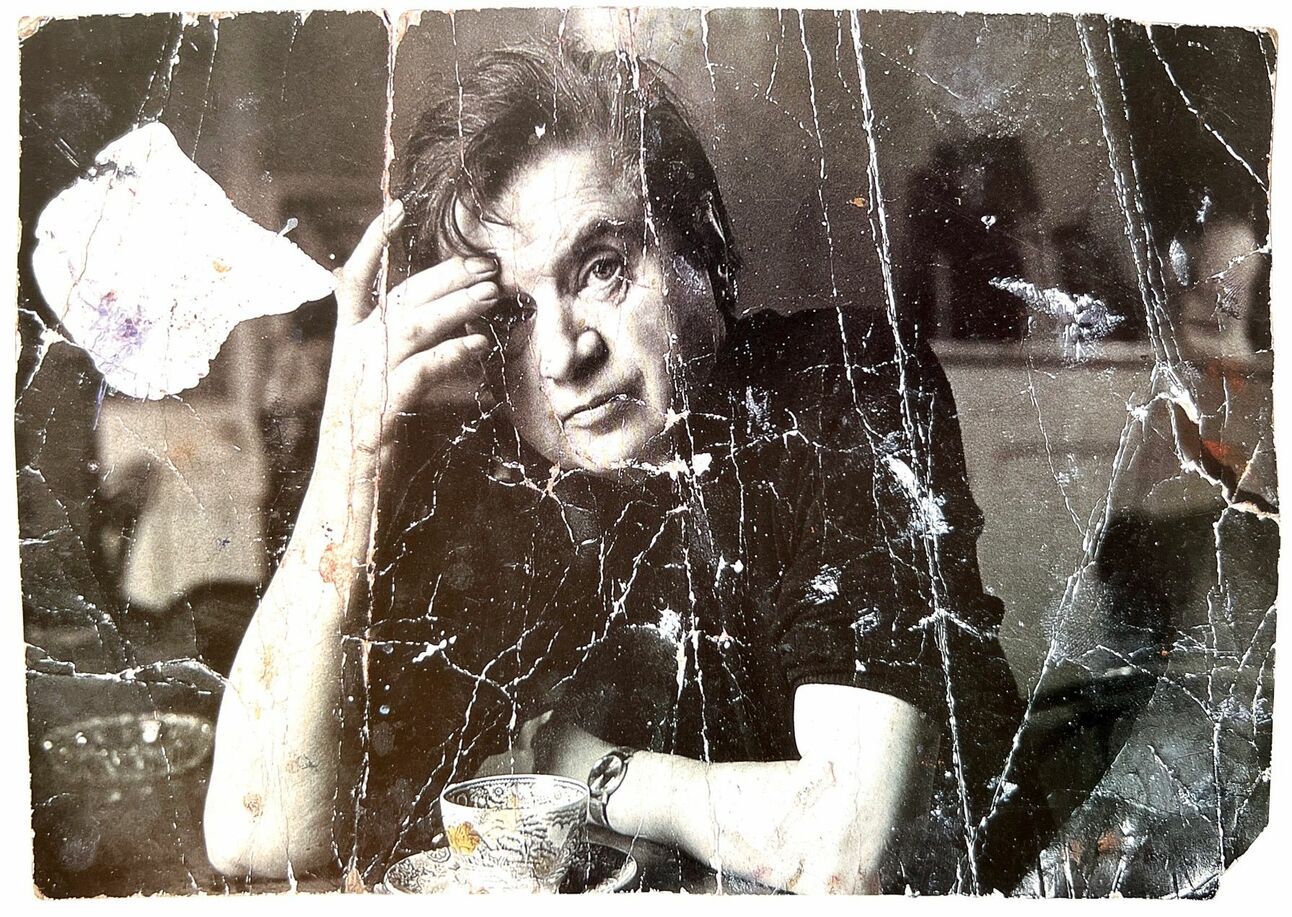

Francis Bacon Leaning on a Table by Henri Cartier Bresson (early 1970s). Three cuttings mounted on a board: Fragment from a book showing two lovers painted by Gustave Courbet; leaf fragment of nude wrestlers by Eadweard Muybridge; fragment from a magazine article about Francis Bacon.

Today, I think the payoff to constructing a pressure-cooker Lebenswelt à la Francis Bacon is probably greater than ever, relative to the sea of noise that defines mainstream internet culture. As in most affairs today, the key constraints are really courage, conviction, and discipline, more so than intelligence, money, or even ex ante skill (you can hardly avoid obtaining skill in this fashion).

Engineer for yourself the smallest possible environment, concentrated as densely as possible with only the highest quality inputs; explicitly re-route all potential distraction-avenues back to one’s chosen craft, such that even when you’re momentarily doing something else you cannot escape the focus of your craft. That is, truly:

"A continuous endeavor.”

Simply live and produce work—produce anything at all, of any quality at first—in such an environment for 10 years, and it’s hard to imagine how you could not produce something exceptional.

To turn coal into diamond, nothing is required except pressure and time.