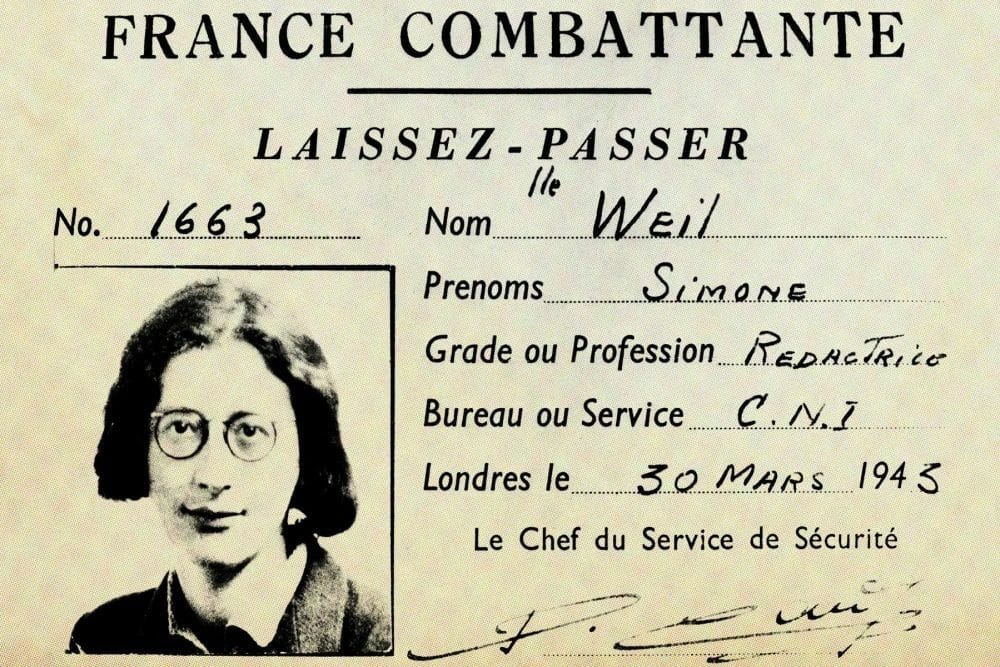

Simone Weil's ID card working for the French resistance

One of the most important facts about attention is that it naturally drifts from object to object.

In his 1890 treatise The Principles of Psychology, William James cites the German physician Hermann von Helmholtz: “The natural tendency of attention when left to itself is to wander to ever new things… So soon as nothing new is to be noticed there, it passes, in spite of our will, to something else.”

If attention is supposed to drift, then why has distraction become such a problem?

Everyone knows today that “attention is the hottest commodity,” attention spans are decreasing, and many people feel they are drowning in distraction.

But why? What are we really saying when we make these claims?

📬

For more like this, subscribe to Other Life. All subscribers receive a little gift in the welcome email.

We’re Not Attention Poor, We’re Attention Wealthy

The total amount of attention anyone can give is roughly fixed per unit of time. Living longer expands how much attention you can dispense, but otherwise, each person only has so much attention to give.

As “content” becomes almost infinitely abundant, the price of attention rises. If the supply of attention is roughly fixed but content (i.e., demand for attention) expands exponentially, one’s attention becomes increasingly valuable.

It’s commonplace to say things like, “attention is the hottest commodity,” except the point remains badly misunderstood. It’s not just that companies work extra hard to get and keep your attention but rather, more positively, it’s that you own an increasingly precious and powerful asset. We get richer for doing nothing. But because of this fact, corporations work extra hard to prevent us from doing nothing.

Now, the ability to do nothing is a rare and difficult feat, hence the high-status and genuinely high value of doing-nothing practices: meditation, reading books, taking long walks, being funny, being beautiful.

We live in a strange civilization where doing nothing is the most impressive, inspiring, attractive, insight-generating, and action-inspiring practice most guaranteed to win praise, insight, and money. Yet, greedily obsessed with winning praise, insight, and money—and lacking any ethical framework for understanding the intrinsic value of attention—most people are unable to access the free riches immediately available to them.

Ultimately, the reason doing nothing is so impressive and valuable is that it tends toward God. As Simone Weil writes in Gravity and Grace:

“Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer… If we turn our mind toward the good, it is impossible that little by little the whole soul will not be attracted thereto in spite of itself."

We love people who do nothing because we intuitively appreciate that their purified attention is nearness to God. This is true even for those who claim not to believe in God. If you've ever admired someone's "focus" or "discipline," you might have been feeling a displaced religious awe. You say that you want to be more focused or disciplined, but really you just want to see the highest Good—and keep your eyes on it.

Will and the Mistake of Pride

The modern individual is alienated from his own riches because he is prideful.

We think we can will the Good into being, but human will is a feeble thing that has nothing to do with the Good. Will is a kind of muscular straining; it's great for rearranging atoms and bits, but it's positively harmful for attending to the Good. As Weil explains:

"The will only controls a few movements of a few muscles, and these movements are associated with the idea of the change of position of nearby objects… What could be more stupid than to tighten up our muscles and set our jaws about virtue, or poetry, or the solution of a problem? Pride is a tightening up of this kind. There is a lack of grace (we can give the word its double meaning here) in the proud man. It is the result of a mistake.

Just as William James saw already in 1890, Weil grasps that attention is naturally fleeting. Distraction is the default tendency of attention. You’re not broken because your attention is always fleeting, just like you’re not broken because you eat too much sugar or look at porn. You’re just human and your nature falls toward all of these things like an apple falls from a tree.

William James' house at 95 Irving Street in Cambridge, MA

Grace and the Good

For Weil, the opposite of gravity is grace. It's not as superstitious as it sounds.

Grace is the reason you're not eating cookies or watching porn every hour of the day. (You could be, and it's not obvious why you're not.) For reasons we don't fully understand, good things occasionally happen. In the shower, we randomly have a novel and useful idea. You didn't will that idea into existence. We don't know exactly why it came, but we know you didn't will it. That's grace.

You only open yourself to grace to the degree that you attend to the Good. This is why Weil says that prayer is essentially just pure focus on the Good. It’s not primarily “talking to God,” it’s dedicating one’s attention to the highest of the high—God. It’s being interested in the highest of the high with the maximum purity one can muster.

Modern individuals think they suffer from attention problems, but we don’t. We’re attention wealthy; we're just impoverished by pride to an even greater degree. We think we do not need grace, or that grace is not real, and we possess ludicrous, child-like confidence in the human will. The result is that we suffer greatly, feeling distracted all the time, unable to see or feel the Good that is already immediately available to us.

Happy Thanksgiving.