For today's issue we have a rare guest post, actually our first ever guest post—by the doctor and soldier Cornelius Stahlblau, author of The Outpost on Substack.

I saw him tweeting about this and I thought a full-length treatment would be of interest to Other Life readers. Cornelius has been an active contributor in the Other Life community for years now, and I've got to know him pretty well, so it's my pleasure for him to contribute the first guest post ever. —Justin

My grandfather had a rare ability in 1960s Spain: he could speak perfect English.

He also had the tough, plucky attitude of young men who’d spent their childhood in war, and adolescence in abject poverty. He landed an engineering job with a US company who was building the railroad in Liberia, then flourishing thanks to post-war America’s hunger for iron ore.

During his three years in Liberia, my grandfather experienced a handful of adventures. He brought souvenirs: a small family of elephants carved in ebony, a beautifully sculpted ceremonial mask. He had an amateur taste for nature and for anthropology, and he talked vividly of crocodile-infested rivers, lush jungles and the barfights that often erupted between the locals and the foreign railway workers, usually Mohawk Indians hired by the Company for their renowned iron working skills.

He also described the daily habits and character of the engineers, who embodied what he always referred to as “the American spirit:” rugged, practical, curious and ambitious. They were for the most part war veterans, freemasons, and corporate men, often living the wild and sometimes depraved lives typical of expats who end up in such places.

My grandfather cultivated these American friendships and business contacts long after he went back to Spain. One of these friendships was with a US Navy officer whom he often hosted at his family’s apartment in Barcelona. Like my grandfather, the man was a geography enthusiast, an interest refined by his professional specialty as a ship navigator. He gifted my grandfather a lifelong subscription to the American edition of National Geographic magazine; a subscription that passed on to me when I was born thirty years ago.

September 1962 edition of National Geographic

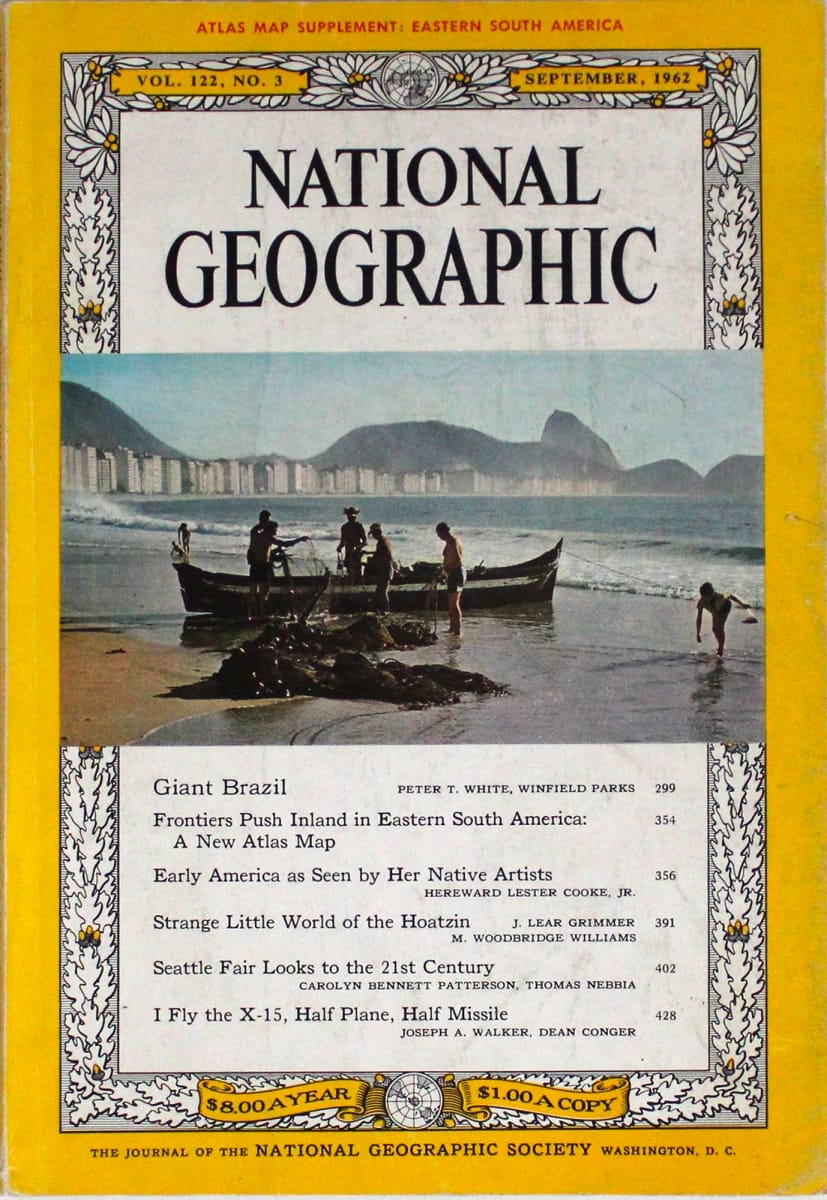

To say I loved the magazine is an understatement. I excitedly waited for each new number, and collected them with devotion. Since the magazine was in English, I did not understand a word, even after learning to read. I still went through every page, looking for pictures of lions, deep sea landscapes and ancient ruins. The famous quality of the photographs and the beautifully-crafted maps fascinated me.

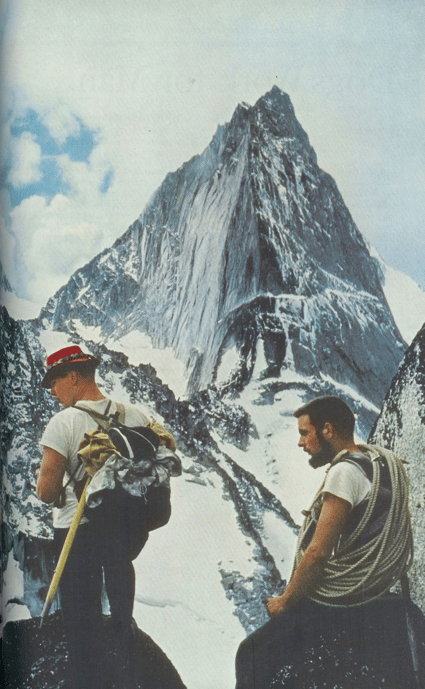

Most of all, I was in awe by what can only be called the badass quality of the stories: reporters seemed to spend most of their time swimming with sharks, braving the elements, climbing mountains, or bribing guerrillas. By age five, I had made up my mind that I wanted to become an explorer and asked for a khaki vest full of pockets as a birthday gift; an appropriate outfit for my future discoveries.

I proudly wore my vest to school, and told my friends stories of little-known marsupial species and the strange customs of uncontacted tribes. My longing for the unknown and yet-to-be-found was not always understood. Once, a puzzled schoolteacher thought it was appropriate to let me know there was little left to be discovered: all the world’s islands were known and accounted for, and the Apollo missions would probably not happen again, even if they had been real (which she doubted). I still remember these words with dismay.

Clipping (year unknown)

Today, if one browses through online reviews of National Geographic, it quickly becomes apparent that the magazine is in a sorry state. Opinions are mostly negative, and vehemently so. Many focus on the spammy marketing strategy, the impossible-to-unsubscribe-from e-mails, and the absurd, equivocal billing policy. Others, however, point to a different problem: the publication has become “politically motivated,” a “non-profit scam,” “another platform ruined by bias,” “90% propaganda and 10% good stuff.” A particularly opinionated customer says the ads are “gay and satanic.”

My subscription did not live to see this sad decline. Once my grandfather's Navy friend died, in 2015, I was offered to renew the purchase, and I didn’t. These were the times right before Trump’s election, and all US institutions, as well as their European clients, were warming up for the upcoming years of memetic warfare. Issues seemed to be every month less about enigmatic ancient civilizations and elusive primate species, and more about contrived discourses regarding “the faces of transgenderism” and the “discrimination endured by the new Europeans.” Compared to a thriving Internet scene filled with obscure anthropology blogs and Twitter accounts posting freely about the world in real time, the magazine seemed stale and politicized.

1982 TV special

The social politics angle does not suit National Geographic well. People who read the magazine usually have retained their childhood’s sense of wonder. They marvel at Creation and want to know more about it. Love for the world and for Mankind is often born out of this primal feeling of discovery: it’s the impulse that spurred the Explorer-Scientists of the last five centuries, whose life’s work led to unprecedented human flourishing.

The old National Geographic celebrated the spirit, and the type of man it produced. It never was an apolitical magazine, as it reflected (and influenced) America’s view of the wider world, and by extension, the West’s. There was, however, something elegant about the way it expressed positions, a certain aloofness with respect to the Current Year™. It focused on its mission: convincing the reader he was part of a civilization still capable of great accomplishments, be it saving the gorillas or mapping the Marianas Trench. National Geographic understood itself as belonging to a tradition, and this was inspiring and fertile, because it tapped into Mankind’s natural desire for discovery.

The desire for discovery is not only a thirst for knowledge, but also for the aesthetic potential it holds. It is correctly recognized as a threat by all enemies of freedom and beauty. Some people simply lack the restlessness and curiosity to look for new islands to discover. When they see that fire in others, they want to extinguish it, lest it burn them or expose them with its light. You know the types: the woke capitalists and the blue-checkmarked propagandists, the grievance studies grifters and the I fucking love Science conformists. People who don’t dream and can’t distinguish between produce and prodigy. National Geographic could not escape their takeover of mainstream culture.

In 2015, the organization became National Geographic Partners, a for-profit organization. It fired a tenth of its 2000 employees and ushered in a new era that culminated in December 2017, when Disney announced it was to purchase 21st Century Fox’s movie and TV assets. These included, of course, the latter’s 73% share of National Geographic Partners. By March 2018, the magazine was already issuing apologies for its previous “racist coverage and colonialist outlook.” Evidently, Disney’s National Geographic now only colonizes your mind (and your purse).

Those who can’t spur the mind to wander will prefer to fixate and hypnotize it. The convergence of the entertainment industry with moral outrage signaling is no coincidence: both entertainment and outrage are forms of hypnosis, similar tactics to capture the mind where it should be set free. National Geographic’s currently bad reviews are revealing: either you buy the propaganda through conviction, or through market saturation and sales harassment.

Fortunately, there are plenty of unexploited opportunities in the current age to escape the traps of rancid, compromised institutions. These opportunities will only grow more plentiful with time. Reality seems to be speeding up, and as the famous Chinese curse says, we might live to see interesting times. My teacher’s idea that the world is wholly mapped might be proven wrong soon enough. War, struggle, and destruction are around the corner. With them, a renewal of restlessness, and an expansion of Man’s future fields of exploration.

The decomposition of Western culture will give way to a new generation of explorers and adventurers, who will reinterpret and rediscover what has been lost. This generation, cut off from the past, will be in an enviable position. It is up to them (to you, reader!) to rekindle the explorer’s love for Creation. A love that cannot be a turned into a political tool, nor an entertainment product, because it’s a secretion of the soul, and the soul belongs to God.

By Cornelius Stahlblau, author of The Outpost on Substack.