In 1955, Harvey Breit asked the great Irish-American writer Flannery O'Connor, "What is the secret of writing?" She said:

"A serious fiction writer describes an action only in order to reveal a mystery."

The writer may only discover the existence of that mystery in the act of writing, she added, and the writer may not succeed in revealing it. But at the very least, the writer must "sense its presence."

To sense a mystery, and try to say something about that mystery—that's one of her secrets.

But if we dig deeper into O'Connor's life, we find a few more secrets, about the beauty of loneliness, the necessity of faith, and how to persist on strange paths nobody else can understand.

In 1945, at the age of 20, O'Connor attended the famous Iowa Writers' workshop.

There she struggled with her awareness that writing is Pride and Vanity. She questioned her calling to write. She was shy and awkward, intimidated by her more handsome and charismatic peers at the workshop, such as Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Hardwick.

Her relationship to God was a relationship that let her transcend the pettiness and distractions of merely human relationships.

For O'Connor, God intersected writing insofar as the writer was dedicated to aesthetic craftsmanship rather than aesthetic frippery.

As she wrote in her journal during her stay at the Iowa Writers' workshop, writing to God himself:

"I must write down that I am to be an artist. Not in the sense of aesthetic frippery but in the sense of aesthetic craftsmanship; otherwise I will feel my loneliness continually . . . I do not want to be lonely all my life but people only make us lonelier by reminding us of God. Dear God please help me to be an artist, please let it lead to You."

By praying to God, O'Connor escaped the desert of human opinion and the trap of short-term fashions.After the Iowa Writers' Workshop, she eventually mixed in to the New York publishing scene via her friendship with Robert Lowell.

Publishers were not interested. Her first novel manuscript kept getting rejected.

She didn't care. She understood and she knew what kinds of books they wanted.

She explicitly decided she was not going to write what they wanted. She believed her vision was good and true. She had faith that if she simply executed, she would eventually achieve the recognition she craved.

Her faith in her own destiny was not blind faith. She also had a mental model of how the world works.

She saw that her transcendence of human opinion, through her relationship with God, would give form to something objectively exceptional:

"I am not writing a conventional novel and I think that the quality of the novel I write will derive precisely from the peculiarity or the aloneness, if you will…"

O'Connor was born in 1925, to an Irish Catholic family in Savannah, Georgia. Savannah was a Protestant and cosmopolitan place.

O'Connor grew up in a time when Catholics were second-class citizens. The stigma against Irish Catholics was not as bad as the stigma against blacks, although perhaps akin to the stigma against Jews.

Some commentators have noted that, being a subscriber to a stigmatized faith, O'Connor found it easier than others to pursue strange and singular lines of inquiry in her work.

Who cares if your writing is rejected when you've already adapted to the experience of rejection as your everyday baseline?

Her father aspired to become a writer, but he never wrote. She speculated that her father never became a writer because he had the people he needed in his life; he had no need to write. She never found the people she needed in her life, so she wrote.

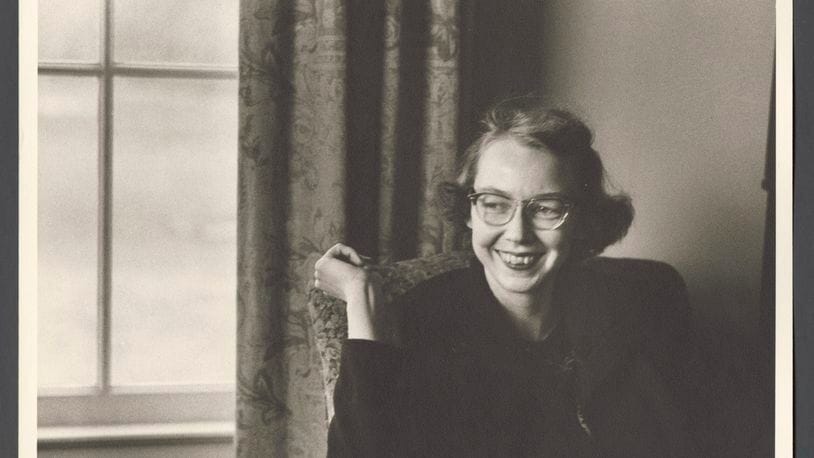

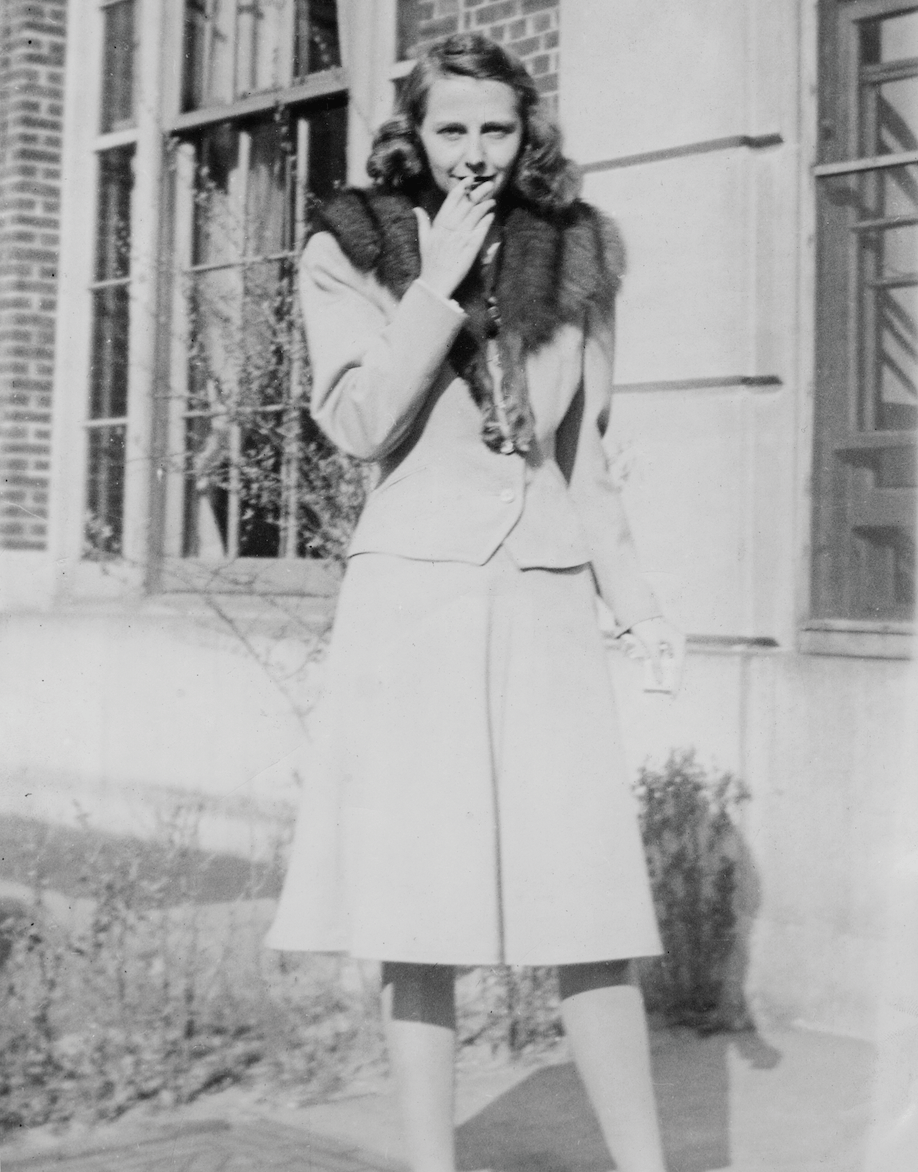

Elizabeth Hardwick (left) and Flannery O'Connor (right) as young adults. When was the last time you heard about Elizabeth Hardwick?

O'Connor once said the reason Southern writers often write about freaks is that Southern writers can still recognize freaks.

Let us hold fast to mystery and persist in something exceptional, however inexplicable it might be to our peers and superiors. Let us recognize freaks.