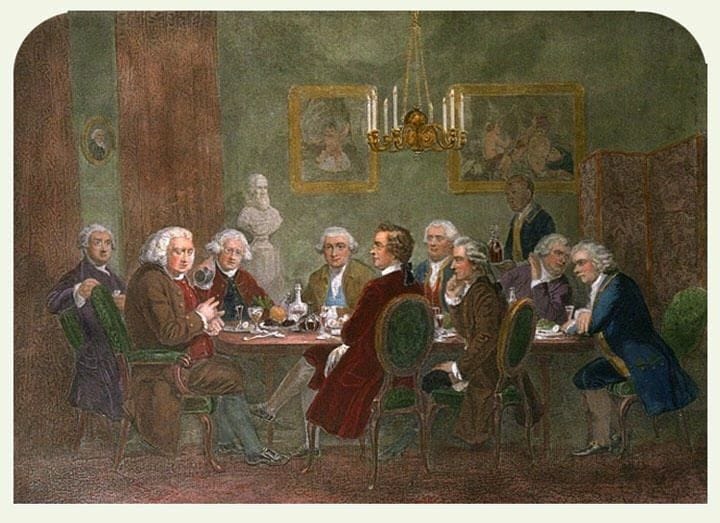

Samuel Johnson's Club. From the left: Boswell, Johnson, Reynolds, Garrick, Burke, Paoli, Burney, Wharton, Goldsmith

Samuel Johnson's Club. From the left: Boswell, Johnson, Reynolds, Garrick, Burke, Paoli, Burney, Wharton, Goldsmith

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) is one of the greatest figures in the history of English letters.

I bet you didn't know he wrote a paid Substack.

For the most part, Johnson studied and wrote through a lifetime of poverty. He was a hypochondriac with nervous tics, who never enjoyed the support of a patron. He came of age at a difficult time for writers, a time when patronage was declining but the modern commercial writing market had not yet taken off.

As we know, his determination paid off. But not many people today know very much about his life or work. So today, I'd like to tell you about the life of Dr. Johnson.

There are many lessons here about the importance of economic self-reliance, how to build a lasting body of work through the open market, why you should never grovel or wait for a wealthy patron, and much more.

As a child, Samuel Johnson displayed traits that would later define him: impressive strength with awkwardness, intelligence with laziness, and a kind heart with an irritable temperament. During his adolescence, he read voraciously from his father's bookshelves.

While his family's financial situation grew dire, a wealthy neighbor helped him enroll at Oxford. There, Johnson's ragged appearance and financial struggles marked him out; he was reckless and uncontrollable, although his wit and knowledge earned him some leniency.

After leaving Oxford without a degree, Johnson struggled with poverty for about thirty years. He became an incurable hypochondriac, with odd behaviors and sudden outbursts. He attempted to publish poems, but the plan failed due to a lack of interest. Johnson's marriage forced him to work harder, but only three pupils enrolled in his academy over eighteen months. His nervous tics cost him job opportunities, and David Garrick later imitated him, amusing London's high society.

At 28, Johnson went to London to pursue writing. He only brought a little money, his play Irene, and letters of introduction from his friend Walmesley. The literary scene in London was not profitable for writers, and only a few, like Alexander Pope, succeeded financially. Johnson's poverty led him to become ill-mannered, unkempt, and gluttonous. He learned to appreciate cheap food and was often insulted, but remained aggressive and determined to pursue his literary career.

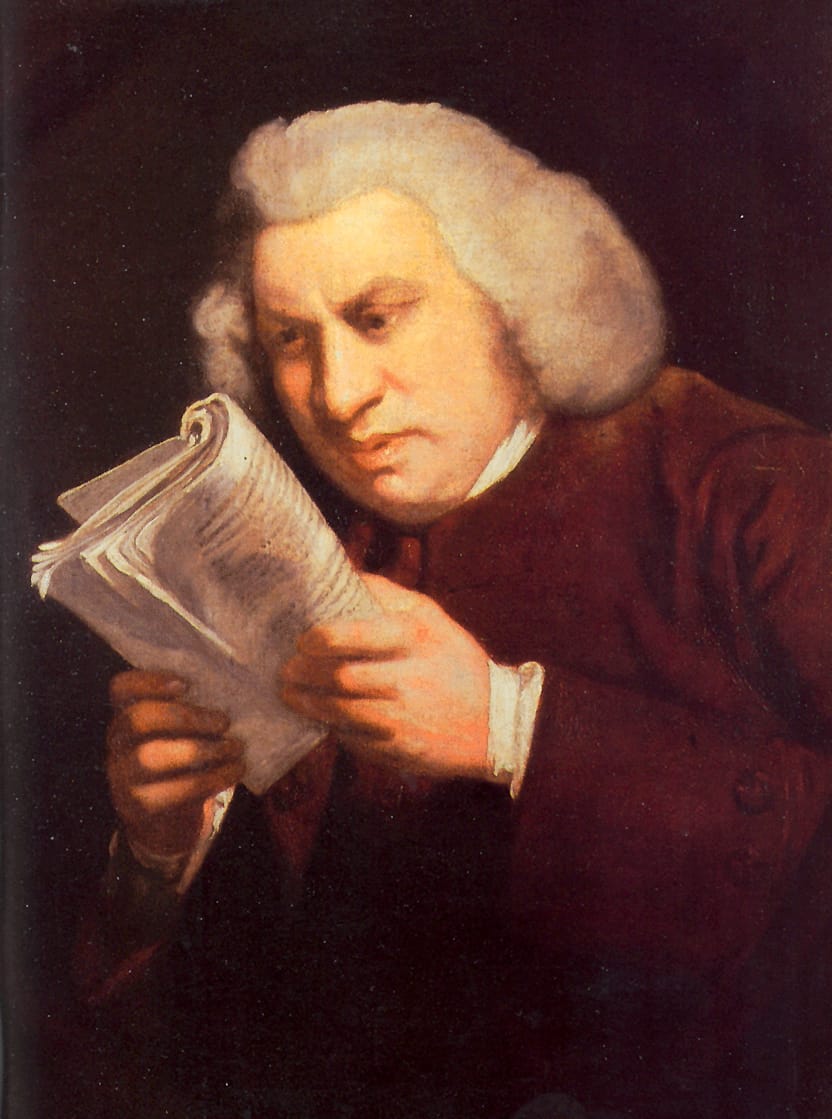

Samuel Johnson (1775) by Sir Joshua Reynolds

Johnson's struggles during his first year in London inspired him to write London, a poem published anonymously in May 1738. Despite receiving only ten guineas for the poem, it sold well and received critical acclaim, with some even claiming that the anonymous writer surpassed Pope. Pope himself praised the poem and predicted that the author would not remain hidden for long. Pope's effort to secure academic recognition for Johnson failed, and Johnson worked as a bookseller's assistant.

Approximately a year after Irene, Johnson began publishing essays on morals, manners, and literature, inspired by the success of the Tatler and Spectator. In March 1750, he launched The Rambler, which was initially praised by some eminent men. Prince Frederick's adviser arranged for copies to be sent to Leicester House, but Johnson did not seek further patronage from the elite. The Rambler was released every Tuesday and Saturday from March 1750 to March 1752.

Many people today think The Rambler was a "magazine," but that's somewhat misleading. It was much more like what we today would call a paid newsletter. First of all, magazines typically compile writing from many contributors; The Rambler was written almost exclusively by Johnson. It published a total of 208 essays covering moral, social, and philosophical issues. The Rambler had a circulation of about 500 copies per issue and earned Johnson about £2 per essay or about $400 in today's dollars. So that's about $800 per week or $3,200 a month. Including some extra sales from collecting the best essays into volumes, it seems he made about £420 total for the two-year project, or somewhere around $90k in today's dollars. In short, The Rambler was a moderately successful Substack.

For his last issue, Johnson wrote while his wife's health was deteriorating. She passed soon after it was published, leaving him heartbroken. He was a devoted husband and he valued her opinion more than anyone else's. He had no other close family, and his laborious work on the Dictionary was primarily motivated by the hope that it would bring her fame and profit.

Lord Chesterfield made efforts to soothe Johnson's pride with kindness, as it was widely assumed that the Dictionary would be dedicated to a nobleman. Writing in The World, Chesterfield praised Johnson's Dictionary, even suggesting Johnson be made the official dictator of the English language. However, Johnson rejected Chesterfield's belated overtures, and the Dictionary was published without a dedication. In the Preface, Johnson vividly described the difficulties he faced in completing the work, which moved even his adversaries to tears.

Dr. Johnson in the Waiting Room of Lord Chesterfield (1845) by Edward Matthew Ward

In 1762, Johnson finally caught his big break. He had a strong antipathy toward the Whig party—he was a Tory—and had even criticized their policies in his work. However, with the arrival of George III, the political climate was changing. Lord Bute, a Tory, offered him a pension of three hundred pounds a year. This change allowed Johnson, for the first time in his life, to indulge his laziness and converse with friends into the wee hours of the evening, without worrying about financial pressures or the printer's schedule.

Johnson had received a substantial sum of money from public subscribers for his promised edition of Shakespeare and had been living off that money for years. Despite attempts to change his ways, he could not break free from his newfound laziness. However, his reputation was eventually challenged in public by a writer named Churchill, who accused Johnson of cheating and inquired about the long-promised book. Just as The Rambler was quite similar to a contemporary Substack, Johnson was accused of being a "grifter" just like writers are today. This accusation had a strong impact on Johnson, and nine years overdue, Johnson finally published his new edition of Shakespeare in October 1765.

In his final years, Johnson battled asthma and dropsy while refusing recommendations from his doctor. He desired to travel to a southern climate but hesitated to use his savings. Friends hoped for an increase in his government pension, but he decided to face one more English winter before his health rapidly declined. Eminent physicians and surgeons attended him, refusing payment. As his final moments approached, Johnson's mind cleared, and he faced the end with composure. On December 13, 1784, at the age of 75, he passed away. A week later, he was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey, not far from many of the great men he analyzed and chronicled throughout his life.

This essay draws heavily from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol. XV.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 471-2.

Earnings data for The Rambler come from WJ Bate, Samuel Johnson: A Biography (1977) and Clifford J. (2004), "Johnson's Rambler and its readers," Huntington Library Quarterly, 67(1/2), 241-262. Conversion and inflation adjustment my own.