A lot of people will tell you that divorce isn't a problem today. They’ll say divorce rates are decreasing and divorce doesn’t harm children, anyway.

The story is much more complicated—a fascinating tale of academic fashions, hidden quantitative dynamics, and mass psycho-social displacements.

In the 1980s, at the same time we became paranoid about kidnappings and satanic child-abuse rings, we became strangely comfortable with parents reneging on their duties to their own children.

Most people in the civilized world, for most of history, believed that divorce harms children. It was only in the 1980s that a small number of unsophisticated academic studies whitewashed divorce, paving the way for today's perception that divorce is just one of many ethically neutral lifestyle choices.

Thanks to advances in social-scientific methodology, especially the rise of adoption studies, we now have compelling evidence that divorce probably does harm young children. The evidence suggests that only in exceptional situations is divorce beneficial for children. Namely, in contexts of extreme marital strife and abuse. But the existence of such rare cases is used, incorrectly, to justify divorce in cases of quotidian marital dissatisfaction. Many individuals now believe divorce is a reasonable solution to mere ennui.

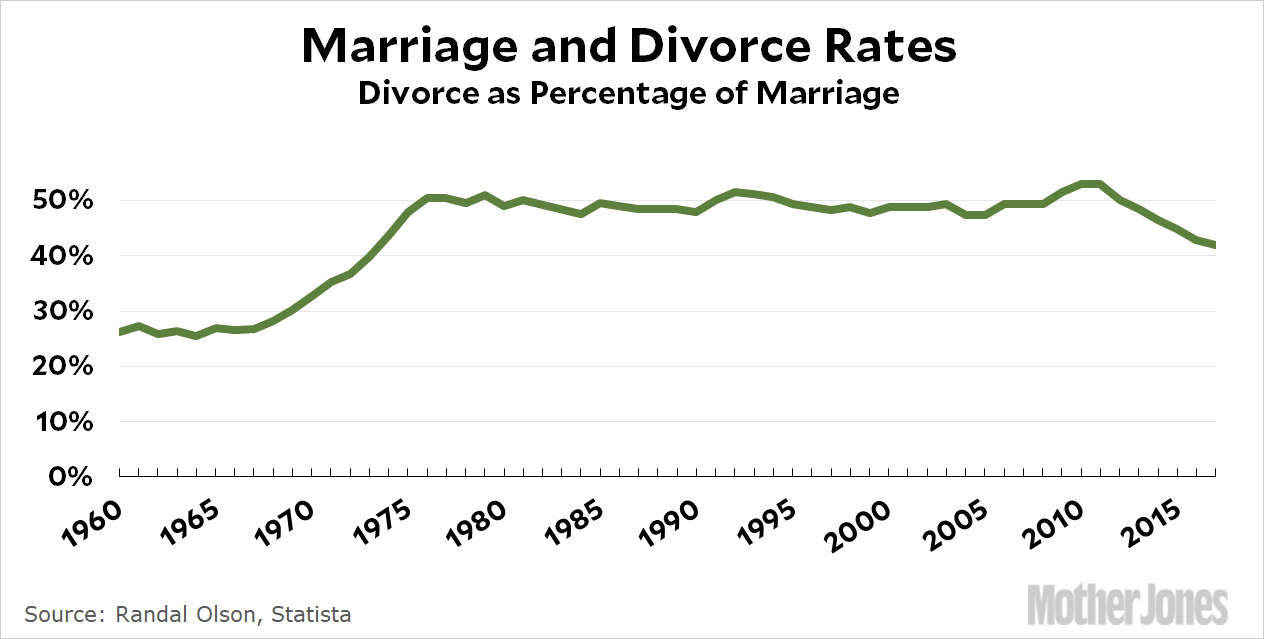

When we look at the data, apparent declines in divorce prevalence over the past few decades are confounded by decreasing marriage rates. As a percentage of marriages, divorces are substantially more prevalent today than they were before the Divorce Revolution.

Finally, the divorce trend has recently mellowed only for upper-class folks. The Divorce Revolution has continued to tear through the working class with greater ferocity every year since the Divorce Revolution first started.

The Story of Divorce by the Numbers

The normalization of divorce in the United States started in the 1960s and became entrenched by what people now call the "Professional-Managerial Class" in the 1970s—especially by female social scientists from the Greatest Generation and the Silent Generation, who were often themselves divorced or in tumultuous marriages.

Barbara Dafoe Whitehead called it the Divorce Culture in her 1996 book of that name.

In 1960, the rate of new divorces was about 9 in 1,000 married couples, or less than 1%. By 1980, that rate more than doubled to 23 in 1,000 or about 2.3%.

The US Divorce Rate Since 1960. Source: Institute for Family Studies.

Now, 2.3% might not seem like a lot, but when extremely rare events double, the social significance can be substantial. For instance, in 2018 there were 103 school shootings. There were 130,930 schools. So only .08% of schools saw a shooting, but that was up from .05% of schools that saw shootings in 2017, so 2018 felt like a really bad year for school shootings. Nobody would say, "The 2018 spike in school shootings was not a problem because the prevalence of shootings remained less than one tenth of one percent."

When naive traditionalists repeat the false meme that "half of marriages end in divorce," they are perhaps clumsily testifying to their correct perception that the divorce rate through the 1980-2010 period was more than double what it was in 1960.

Another reason that graphs like the graph above feel underwhelming, and understate the problem, is that they don't zoom out enough.

Consider below the longer time-series, which goes back to about 1870. Ignore World War II because that was an outlier event causing extreme and exogenous family disruption.

Notwithstanding WWII, it's easy to see that something remarkable happened beginning around 1960. We are somewhat recovering now, that's true, but we're still at levels of divorce that are high from a longer-term historical perspective. Many of our parents (and now grandparents) were married or divorced in the 1970s or 1980s, so that divorce spike after 1960 may still hold great emotional interest for Millennials and Zoomers today, even if the 1980s divorce mania is gradually re-equilibrating to the historical trendline.

Marriage and Divorce Rates in the United States, Since 1870. Source: Robslink.com

Another consideration is that, if fewer people are getting married, then we should expect to see fewer divorces per capita in the population. We would need to look at divorces as a percentage of marriages. Also, there may be some selection effect where the married couples who are able to overcome the cultural fashion against getting married are, on average, better marriages.

So it's not a rosy picture for married life in America if the decreasing divorce rate is partially driven by people being less likely to marry at all.

If we look at the divorce rate as a percentage of the marriage rate, we see that since the late 1970s, for every 2 new marriages we see about 1 new divorce. This ratio roughly doubles between 1960 and 1980, and persists more stably into the present. It dips from around 2010 but less so than the popular "divorce is no problem" graphs you sometimes encounter today.

Divorce as a Percentage of Marriage Since 1960. Source: Mother Jones.

The Divorce Lobby

The most famous feminist rabble-rousers like Betty Friedan are not the stars of this plot. Friedan and her ilk were unabashed activists and their work resonated primarily with women who were intellectually starved as homemakers, whose kids were often already adults. Furthermore, Friedan's object of scorn was not really marriage, it was the lack of meaningful and well-paid work opportunities for women outside the home.

The Divorce Revolution was manufactured primarily by career academics who published research papers and mass-market books extolling the benefits of divorce and downplaying its harms.

Jessie Bernard's The Future of Marriage (1972), for instance, purported to show that marriage was beneficial for men but harmful for women. Bernard (born in 1903) was a respected academic expert and quickly became a media star, so she enjoyed broader appeal and influence than someone like Friedan. The book made rather extraordinary claims, such as:

“To be happy in a relationship which imposes so many impediments on her... a woman must be slightly mentally ill."

The book's evidentiary basis was dubious. Today we know that cross-sectional surveys cannot alone furnish causal claims, let alone extraordinary claims like the one above. Whitehead notes that her claims were quickly challenged by other academics, although that’s par for the course in academic research. More glaring, however, are Bernard’s rather loose logical and rhetorical standards. She seems to dismiss alternative data sources that observed equal levels of satisfaction and dissatisfaction among men and women as something akin to Marx's false consciousness: not inconsistent with her argument but only proof that marriage indeed made women mentally ill. To be fair to Bernard, a lot of social science in the 1970s sounded like this.

We should avoid the ad hominem fallacy, but biographical data often carries meaningful signal about the context and motivations of an author. Bernard herself married an older man when she was 22, a more successful academic 23 years her senior. After struggling to succeed in her own academic aspirations, she separated from her husband for a period of 4 years from 1936 to 1940. They then reunited and started having kids, all about 30 years before she published The Future of Marriage. Is it unfair to wonder what was really going on with this woman?

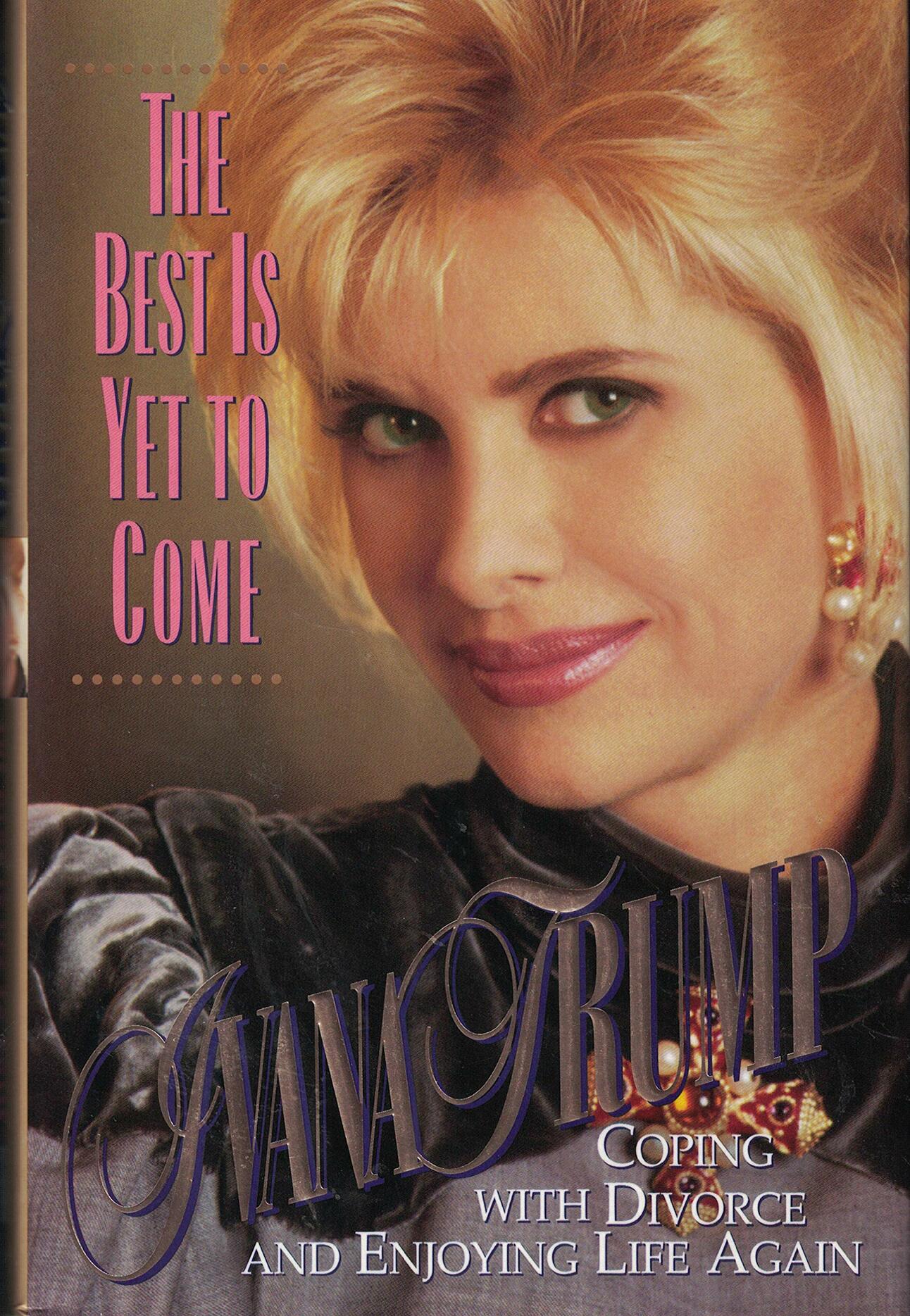

From the 1970s to the 1990s, books about divorce typically had titles like The Best is Yet to Come, or Growing Through Divorce, or Our Turn: Women who Triumph in the Face of Divorce.

Constance Ahrons, who published The Good Divorce in 1994, was another heavy-hitter in the academic wing of the divorce revolution. According to Ahrons, divorce is only a problem because society stigmatizes it. The real problem is "divorcism." If you call a family with divorced parents a "broken family," that's divorcist. Instead, you should call it "binuclear," another fantastic coinage of hers. Instead of "ex" and "step" as prefixes, she suggested we use the term "fuzzy kin." I'm not kidding!

Born in 1937, Ahrons enjoyed an illustrious academic career and appeared on national television frequently, everywhere from Oprah to Good Morning America.

Divorced twice herself, Ahrons describes one of her divorces in The Good Divorce:

“I was the one who left, and for two miserable years my husband and I battled constantly over custody, visitation, and child support. There were private detectives, a kidnapping, several lawyers, and two years of legal fees that took me the next ten years to pay off.

This might seem like a surprising admission for an expert on Good Divorces, but it’s a common refrain among the academic, female divorce lobbyists: Their own extreme marriage problems are recast as credentials. "We know exactly what not to do."

Call me crazy but maybe a woman embroiled in a world of private detectives and kidnappings is not well positioned to be a marriage coach. It did not stop her and it did not stop anyone from listening.

Lynette Triere, who wrote the classic Learning to Leave (1982), now runs a lovely consulting agency called Leaving and Being Left. On her agency’s website, she positively boasts about her own divorcing ineptitude: “I made every mistake possible trying to get through the divorce process.” Weird flex but OK.

Exploring this wave of pro-divorce literature as a middle-aged man in 2021 is like walking through a carnival funhouse run by Nancy Pelosi. Grinning octogenarians with girlboss eyeglasses and younger men on their arms—son or lover, does it really matter?—articulating the most ponderous pronouncements.

Lynette Triere and Constance Ahrons

Triere, now at 80 years old, says that the mission of her agency is to “help women and men navigate the difficult terrain of divorce while avoiding the pitfalls of a breakup.”

What did she mean by this?

The Effects of Divorce

Nothing above matters if divorce is innocuous. So is divorce harmful?

Even if we mustered correlational studies suggesting that divorce is associated with harmful outcomes for children, it could plausibly be due to genetic confounding. Genes that increase the probability of a couple divorcing could also depress children's outcomes, even if the divorce experience has no effect.

Ideally, we could find someone whose personal bias leans toward divorce not mattering, who understands science, and who has read all of the recent research. Then we could just ask him. If he thinks divorce is probably harmful, then it's probably harmful.

In Scott Alexander's review of the matter, The Dark Side of Divorce, his initial belief was that genetics trumps parenting—and therefore genetics would likely explain away any perceived effect of divorce.

Once he reviews the most important adoption/twin studies, he has to walk back his initial expectations. One study found no difference in divorce effects among genetic and adopted children. Another study produced mixed results, so it was inconclusive. A third study found support for the claim that divorce causes harm; that negative effects from divorce were mostly limited to children whose parents got divorced when they were alive, with little effect observed among children whose parents got divorced before they were born. Finally, among children of identical twins, a child of a divorced twin will do worse than a child of a non-divorced twin, on average, suggesting an environmental explanation.

So even Scott Alexander seems to believe that divorce probably causes some negative effects, specifically through the psychological stress of family strife that occurs around divorce.

But there is one final wrinkle about divorce. The mainstreaming of divorce has ravaged the working classes much more than the upper classes.

The upper classes tired quickly of the 1980s divorce mania; they stopped accelerating divorces after the spike from 1960 to 1980. They tested the alternative hypothesis that "divorce is totally good, actually" and they failed to reject the null. They probably saw the harmful effects, especially on children, and then spread the word to all their mates in Cape Cod.

But the poor people, they went full-throttle on divorce and never looked back.

Divorces Over Time, by Class. From Coming Apart by Charles Murray

The working class tested the divorce hypothesis but didn't understand science, so they stupidly inferred that their initial divorce dose just wasn't big enough. "Marriage is so oppressive," they reasoned—because Jessie Bernard and Constance Ahrons said so on Oprah—"that we must keep divorcing until we're fully liberated, happy, and rich!"

When experiences emerged that contradicted this theory, they did not spread the word around their yacht club because they did not have yachts. What they did have was television, and later internet, both of which offer an endless supply of divorced people on yachts.

Divorced People on Yachts: Ben Affleck, Jennifer Lopez, Nicole Kidman, Jennifer Aniston, Angelina Jolie, and Brad Pitt

Conclusion

A few upper-middle class women in the 1980s declared invalid an ancient and universally acknowledged duty, with no warrant other than a few correlational studies. When the divorce culture turned out uglier than they imagined it would, the upper-middle class corrected course but never passed the memo to the working class.

The Divorce Revolution may have begun with innocently naive research accidentally elevated to prominence by impersonal media selection effects, but the continued trivialization of divorce today can only be called sinister, given what we know now.

Subscribe for free, the Other Life newsletter has no paywall. ;-)