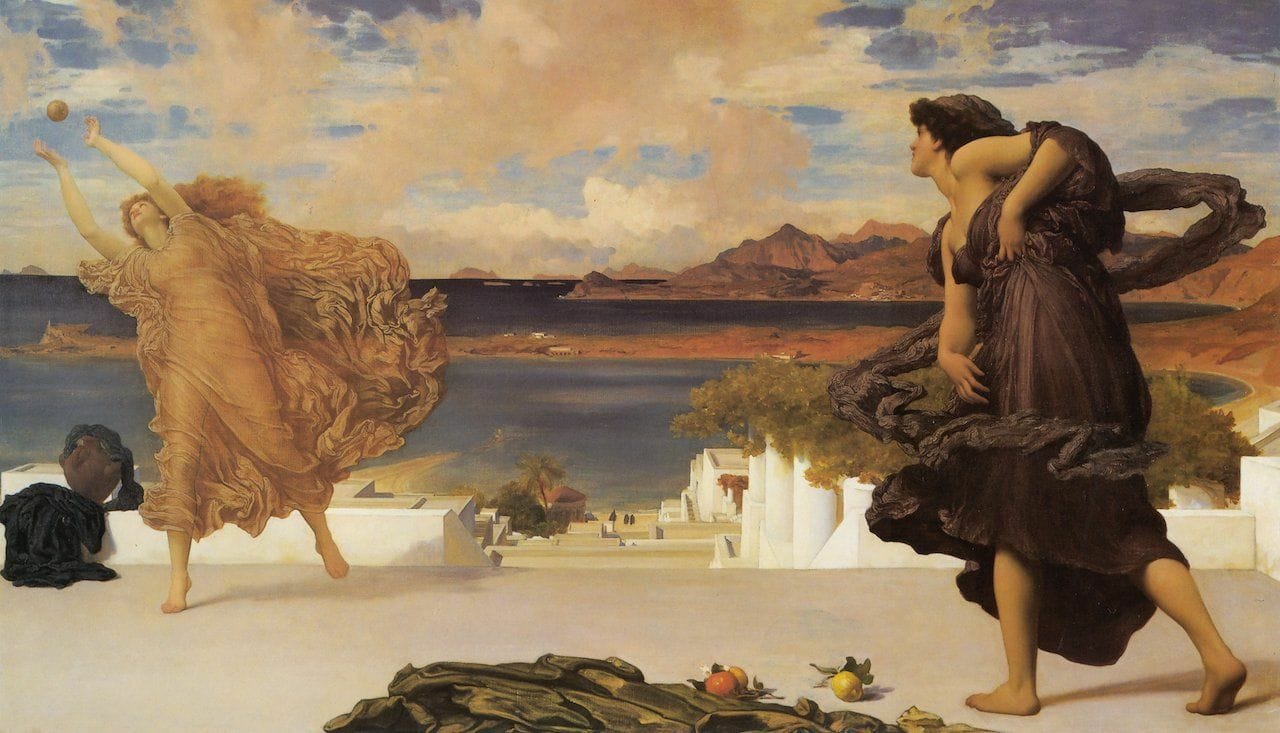

Greek Girls Playing Ball (1889) by Frederic Leighton

In the Symposium, Socrates refuses to have sex with Alcibiades, even while they are in bed together.

In the Phaedrus, the lovers are chaste.

Apparently, the Socratic method has been updated.

A recent article in The New Yorker profiles academic Agnes Callard, who left her first husband Ben for a graduate student named Arnold. Agnes Callard specializes in ancient philosophy and ethics. She and Ben have two children together.

To start, here's the story of how this married woman began a relationship with a graduate student. Does anything seem missing here?

"To celebrate the end of the term, Agnes had made cookies for her students, and she gave an extra one to Arnold, a twenty-seven-year-old with wavy hair that fell to his shoulders, who was in his first year of the graduate program in philosophy. As Arnold ate the cookie, Agnes, who was thirty-five, noticed that he had “just this incredibly weird expression on his face. I couldn’t understand that expression. I’d never seen it before.” She asked why he was making that face. “I think I’m a little bit in love with you,” he responded."

Somehow they moved from the classroom into her office, but there are no contextual details. The details would tell us a lot about what's really going on here. As it's told here, it's just not psychologically plausible and I'm forced to infer that the omission of all detail is probably covering up at least some degree of affair-like behavior before the divorce.

"How has it come to pass,” she writes, “that we take ourselves to have any inkling at all about how to live?”

Is this not obviously vacuous and implausible speech? Certainly, we must have more than an inkling of how to live because the experiment has been run billions of times over thousands of years of recorded history.

"Sometimes it seemed to Agnes that the universe had been prearranged for her benefit."

Is she inferentially incompetent, a victim of apophenia, or does she really assign a non-zero probability to the existence of a supernatural force parting the seas in honor of her personal excitement?

"Arnold said that the first time Agnes’s sons came to his apartment, 'I remember watching them play on the furniture and suddenly realizing: this is the point of furniture.'"

Ah yes, the point of having furniture is for another man’s children to play on it. Another utterly vacuous observation.

You know what's going on here, right?

These people are horny.

I don't wish to be crass, that's just what it is.

Have you ever been horny for someone? You can say all kinds of stupid stuff, at length, for a while. How does the author of this article not understand what's going on here?

"One of the things I said very early on to my beloved was this: ‘I could completely change now... There is suddenly room for massive aspiration."

Why does she need a new partner in order to change herself? This seems like a worthy philosophical question for someone wishing to live an examined life.

Is loyalty a good? If loyalty is a good, how should it tradeoff against freedom and enthusiasm?

Good questions, but these ones are not horny enough!

If a married man of 35 "aspires" by opening his heart to a student in her twenties, it is rightfully mocked as an immature way of coping with senescence. The "midlife crisis" meme testifies to this obvious pattern. But when a writer for The New Yorker catches wind of a female professional doing something that men are notorious for doing in a pathetic fashion, well now it must be fascinating, brave, and heroic. I suspect the author and Callard both drink this Kool-Aid because, otherwise, the simple and direct reading of this article is shockingly cruel to Callard (if one is not drinking the ladies' Kool-Aid, that is). And Callard on Twitter was pleased with it.

As I read this story, I see no reason why the null hypothesis should not be the "midlife crisis" hypothesis: Leaving her spouse for a younger man is just basic, insecure selfishness. It's not uncommon in our rational and secular world. Surely this must be the base case for what's going on here. So I expected the article to furnish interesting evidence of something different. But there is nothing different. Even Callard's words, they don't really even purport to say anything different. She just says them grandiloquently, and seems to believe that adding a layer of grandiloquence is enough to make her quotidian midlife crisis something different, something distinguished and interesting.

It's possible Callard is saying and doing something different, and the author of the article simply failed to reflect it, but I doubt that because Callard is quoted at length. Her own words essentially boil down to: "The good life means pursuing my appetites and using the excess heat to generate words." All the power to her, but this strikes me as a rather weak ethical theory. Go look at her words in the article and tell me with a straight face that there's anything more sophisticated going on there. Even her collaborator Robin Hanson made a similar observation.

Callard was not upset or disappointed with the profile, which says to me that she must not have other key substantive arguments neglected by this piece. Therefore we should take this profile at face value, and understand it as a fair, balanced summary of Callard's ideas and personal life.

This part is revealing: "Her thoughts felt like 'mushy dots,' but, through conversations with Arnold, they had started to solidify. 'It was only then that I felt I could settle on things and start to complete a thought,' she said."

She likes the younger man Arnold because his age and his lower status make him a more compliant and passive sounding board than her husband, who—as a peer and professional philosopher in his own right—probably does not see himself as a device for increasing his wife's word count.

When I was 21, I briefly dated an attractive and professionally independent woman who was 30, and I was more than happy to be used as a device for whatever she wanted. Fortunately for that woman, she was philosophically mature enough to realize I was never going to be marriage material for her and our fling ended pretty quickly. Agnes Callard eventually learns this same lesson, but only after a few years into her marriage with Arnold. With all due respect to Callard, she is patently less philosophically wise than the kindergarten teacher I dated in my twenties.

"Next year, we are co-teaching a course on paradoxes," says the first husband with respect toward the second husband.

Of course, this story would not be complete without academic nepotism. No offense to Arnold, who honestly comes off as kind of wise, except for the "seducing a married woman" part. But as he says in the article, he's not ambitious. And you don't really make it very far in academia today if you're not ambitious. Therefore, we are forced to infer his modest position at the University of Chicago is thanks to nepotism. To be clear, this is not particularly scandalous; such things are sometimes even official and called "spousal hires." A great gig if you can get it!

Anyway, she eventually grows dissatisfied with Arnold and now they're talking about going polyamorous. "I think I never realized how fundamentally selfish I was before I met Arnold... I’m just really not able to be much less selfish than I am," says Callard.

Can you believe it? All of this time and energy, just for one big, round-trip flight back to the appetites. She pretty much admits that her decision to leave her husband for a graduate student was intellectually an error or miscalculation, caused by her appetites overriding her reason. But the implication is not that she must return to an inquiry about her appetites, and perhaps a restructuring of her attitudes and habits toward a greater alignment with virtue, no—that would not be fun. That would not be horny. The implication is that she should go find new romantic excitements, of course. Frankly, why would she come to any other decision?

All of the men in her life have been incredibly generous to her at every turn; it seems that nothing bad ever happened to her from making her massive miscalculation, so why would she change her attitude or approach to life?

This story is one of the most dramatic proofs that independent, professionalized women today, in the feminist era, are cognitively destroyed by the absence of social error-correction. Here you have an incredibly educated and brilliant woman who accidentally wasted 10 years of her life on a meandering, circular quest that makes Don Quixote look like Elon Musk. Only to arrive at basic truths that were written clearly in many of the texts she already knows well.

It is one of the most remarkable case studies of the fact that women require at least a few strong men who love them enough to enforce the contours of objective reality around them.

When Agnes said to Ben that she wanted a divorce, Ben should have had the strength to dissuade her, for her own well-being. He should have laughed at her, and if that failed, then he should have started flirting with grad students until Agnes equilibrated. In this way, Agnes could have learned the lesson she would later learn, but much faster. But of course he immediately endorsed her divorce proposal, so Agnes infers her instincts must be reasonable.

When a woman is surrounded by men who abide by all of her ideas, no matter how absurd, that woman is doomed to make mistakes over and over again. Such women now disproportionately end up as writers for New York magazines, or writers of philosophy books, where they generally focus their craft on rationalizing their own confusions. Rachel Aviv's profile of Callard is such a masterpiece because everything I'm saying is explicitly corroborated in the text. One does not have to read between the lines.

"Arnold saw Agnes’s first book, 'Aspiration,' which she began writing the year after they met, in part as an attempt to make sense of their experience of falling in love... Agnes said that maybe that would be the title of her book about marriage: Marriage Is a Preparation for Divorce."

How is it possible that academic philosophy is not just decreasingly correlated with wisdom, but now inversely correlated with wisdom?

Agnes Callard has not merely gone astray from the core insights of Ancient Greek ethical thought (on which she is an expert), it is as if her education and professional milieu allow her to run all the faster in the exact opposite direction of anything that philosophy could possibly teach us.