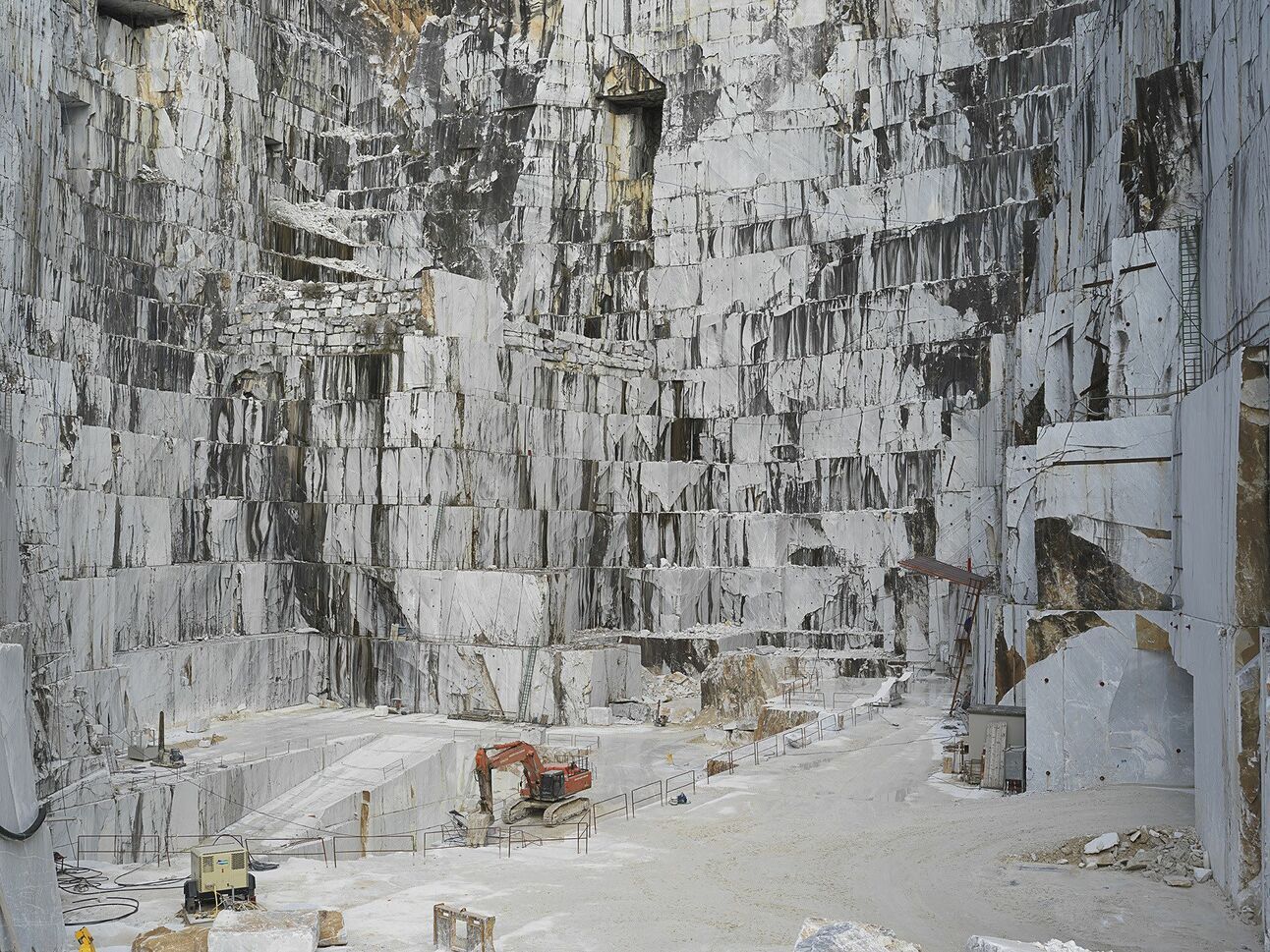

A quarry

Welcome to Signs of Life, a periodic roundup letter from Other Life, the coolest newsletter in the world. If someone sent you this, subscribe for yourself here.

In this issue:

The Sweet Smell of Success

Thrasher Magazine

The ESG Scam

My review of The Network State

Come to the Imperceptible Mansion in November

This will be our third annual mansion weekend, which will be held on the California coast near San José on the weekend of November 4-6. The image shows the actual site.

We once called this "based mansion," but I'm over that...

This started as a small experiment in Los Angeles two years ago, it grew into a larger event last year in Austin, and now I guess it's officially an annual tradition.

This unique weekend getaway/conference/retreat is typically a combination of two types: Independent writers and creators interested in exiting institutions, and philosophically inclined software engineers interested in building exit technologies. Anyone is welcome to request a spot, as long as you're working on something interesting, but this summarizes the center of gravity.

This is about 80% booked now. If you want to come, just drop your email at the link and we'll email you shortly.

The Sweet Smell of Success

I'm the first to admit I usually don't love movies from before the 1970s.

They're usually hard to finish: Slow, uninteresting, they feel irrelevant. You can pretend you’re a sophisticated vintage film lover, but I won't. That shit is usually boring!

Yet one film I recently enjoyed is The Sweet Smell of Success (1957). It's a riveting look at a dimension of media history that's been totally forgotten today:

The unparalleled power of top newspaper columnists during the golden age of the American newspaper.

In the film, Burt Lancaster plays such a columnist, modeled after the historical figure Walter Winchell (1897-1972).

You've probably heard of William Randolph Hearst but you've probably never heard of Winchell,

Winchell's daily column was read by 50 million people per day from the 1920s into the 1960s.

His Sunday night radio broadcast was listened to by 20 million people from the 1930s into the 1950s.

Susan Harrison and Burt Lancaster in The Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

Another reason I liked The Sweet Smell of Success is that it reveals the nature of media politics, which today is covered up underneath several layers of disingenuous, prosocial moralism.

The second main character is a publicist played by Tony Curtis. The publicist is paid by individuals and companies who want to get their names into popular columns (covertly; we're not talking about "sponsored posts" with "brand partners").

How do publicists get their clients into top columns? Can't individuals and companies just pay off the columnists directly? At their core, publicists are more like mafiosi than the media professionals we call them today, or so this film suggests.

Publicists get their clients into columns because they feed columnists juicy gossip in exchange, or else they turn to any number of other underhanded tactics like blackmail and bribery. Today, the same ethical structure persists but it's now absolutely implicit and unspoken.

The joy of this film is that, in the 1950s, apparently, this was all explicit. The publicist character is a spineless mercenary who wants money and power and nothing else—and he doesn't hide or deny it.

The Sweet Smell of Success is a thrilling and illuminating film, which exemplifies one of the only good reasons to watch old movies: To see and hear and feel the relatively demystified version of a contemporary reality, in one of its previous, naive forms.

I found it Amazon Prime Video.

What's your favorite movie from before 1970, which is actually great to watch? Hit reply. Don't give me film school flicks you're supposed to like, which are actually snoozefests. Give me old films you still find genuinely riveting today.

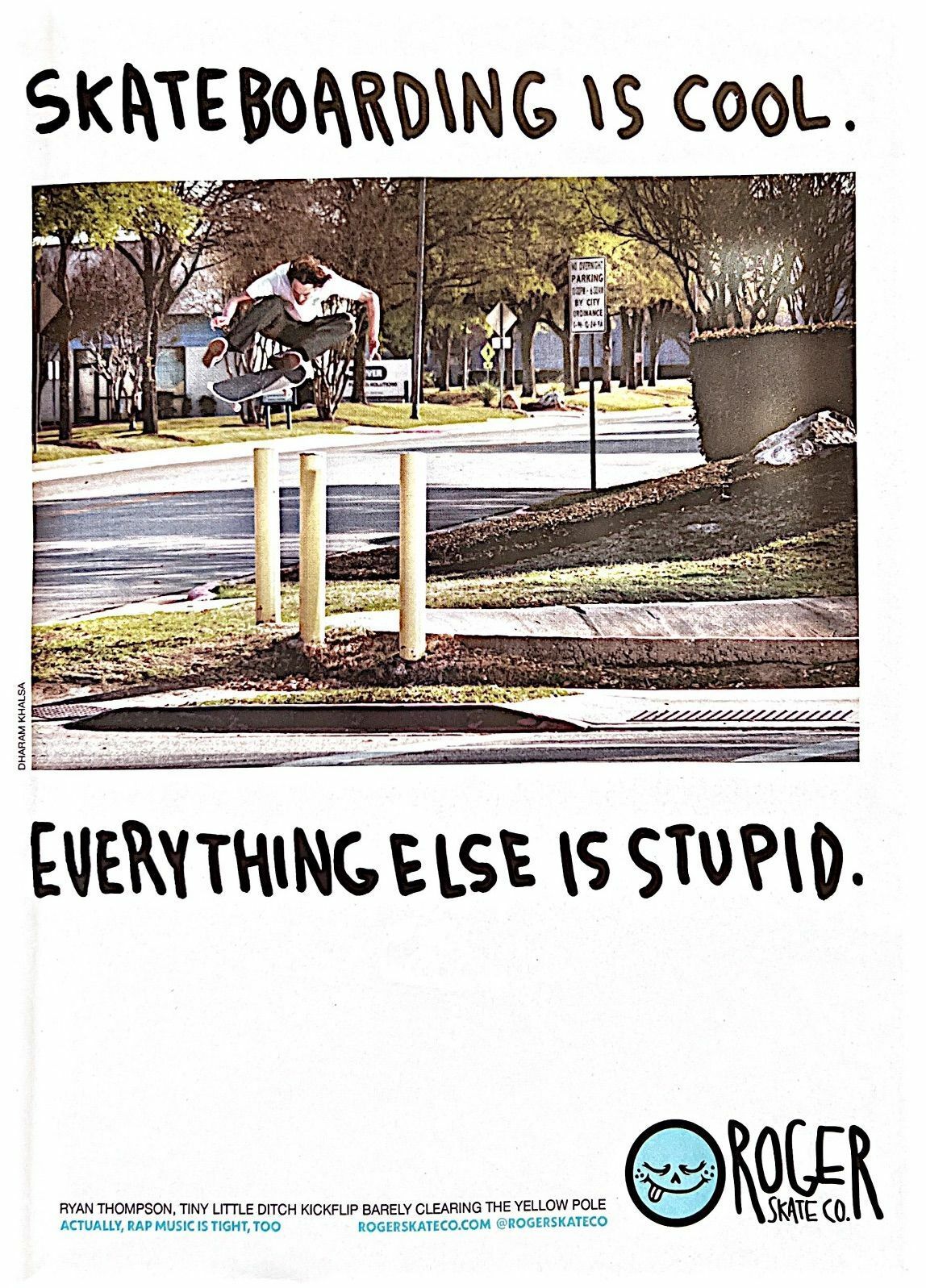

Advert from Thrasher Magazine.-

I recently picked up an issue of Thrasher and thumbed through it on a lazy Saturday morning. I was completely dumbstruck by how much joy it gave me. It's hard to express the impact skateboarding has had on me; most of my adult character today was formed skateboarding non-stop from age 9 to 16. Skateboarding is a structurally anarchist sport: Doing it anywhere is defying a cop somewhere. I immediately resubscribed to the print edition, after a hiatus of about 15 years.

Other Life #203: The ESG Scam

Marty Bent is the founder of TFTC.io, a media company focused on Bitcoin and freedom in the digital age. We discuss the "ESG" movement, how Marty built his media company, and how he's now building a natural gas company with Bitcoin mining.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your preferred podcast player.

A New Type of State, A New Type of Book

Issue #2 of the Mars Review of Books includes my review of Balaji Srinivasan's new book, The Network State.

I hope readers will find it balanced; helpful for judging the book's high volume of ideas. On the book's weaknesses, I do not pull punches. I'm equally emphatic about the book's strengths. This is a fun, stimulating, and in many ways impressive book by an admirable thinker, so I just tried to put these things in perspective.

Here is one paragraph that might be a decent TLDR.

The Network State is recommendable as social theory insofar as the inspiring quality of its wildness generally redeems its frequently thin preposterousness, but it is perhaps most remarkable as a work of applied media theory. Srinivasan’s explicit wagers on the future of technology and society are worth knowing, but the book’s implicit wagers about the future of book publishing seem more adequately backed.

You can read my whole review alongside pieces by Tao Lin, DC Miller, and others. You should buy the Mars Review of Books in print.

Abide by your spontaneous impression with good-humored inflexibility

Autumn Forest (1876) by Ivan Shishkin

"A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his. In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with certain alienated majesty. Great works of art have no more affecting lesson for us than this. They teach us to abide by our spontaneous impression with good-humored inflexibility then most when the whole cry of voices is on the other side. Else tomorrow a stranger will say with masterly good sense precisely what we have thought and felt all the time, and we shall be forced to take with shame our own opinion from another." —Emerson